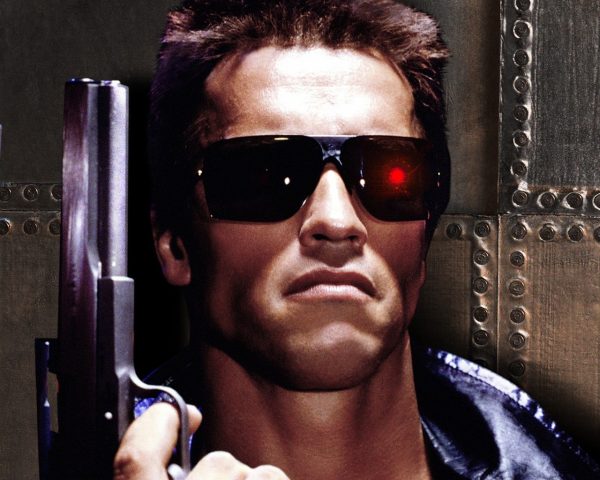

When most people think of the dangers of artificial intelligence, this is probably more or less what comes to mind:

Computer-literates and paranoids might raise (legitimate) privacy concerns and mention uncomfortable cases like the teenager whose parents learned she was pregnant when a machine learning algorithm started sending her parenting advertisements based on her purchasing habits.

That is not my biggest worry, though.

The reason artificial intelligence has a chance is because people are extremely bad at making judgements. We base our decisions on our own memory, which is only very loosely based on reality, on facts that are really just disguised prejudges and opinions, and on heuristics that are largely wrong.

The reason artificial intelligence has a chance is because people are extremely bad at making judgements. We base our decisions on our own memory, which is only very loosely based on reality, on facts that are really just disguised prejudges and opinions, and on heuristics that are largely wrong.

We like to describe our memory using physical metaphors, which might give insights to how our memory might work and how the metaphor works, but also serves as a source of much confusion. Our memory has been described as railroad systems with memories are transferred around on tracks, we a video recorder keeping track of past events, and as an internet of neurons which can reliably store and transfer information. This is very wrong; we such at realling stuff from the past. We extrapolate from our feelings and present much more than we accurately recall. We summarize our experiences using pretty much just our most extreme and last emotion, completely disregarding average emotion and duration. People have in experiments shown to reject an unpleasant experience lasting for 60 seconds in favor of an unpleasant experience that lasts for 60 seconds followed by a mildly unpleasant experience lasting 30 seconds.

We are wildly biased about most things, and it interferes with our judgement. We disregard or reject information that we disagree with and largely base our opinions on information we already agree with. We reinforce our preconceived opinions using these facts and rationalize that they are really facts. We get emotionally invested in things which should have no emotional value; for example, we are willing to pay less for an item than we require to sell that same item once we own it. Shops abuse that by letting you touch items or – better – try them (e.g., trying on clothes), which instills that feeling of ownership and raises perceived value. We tend to make decisions on first impressions; research has shown that job interviews were based largely on first impression rather than the actual interview and they are therefore largely useless to both parties. A football fan will be very bad at judging the chances of their favorite team winning the game tonight.

As our minds are immensely limited, we tend to use heuristics. One very grave one is the availability heuristics: we judge how common something is by how easy it is to thing of examples; a standard example is “does the English language have more words that start with the letter K or that have the letter K as the third letter?” The correct answer is that there are more with K as third letter, though our intuitive response is that there are more starting with K because it is much easier to think of such examples. There is in fact three times as many words with K as the third letter as there are starting with the letter K. This can be seen as people thinking flying is more dangerous than going by car (because we rarely hear about car accidents but “often” about plane accidents), that Zika, Ebola, Bird flu, Pig flu, etc are things that matter directly in any way at all to a first world citizen.

So, people are really bad at making decisions, and a computer can conceivably be better than “very bad.” And that is in fact true. Artificial intelligence is already in many ways better at making decisions than humans. It can be simple check-lists made by humans for job applicants or it can be complex self-learning systems that dig thru large quantities of existing information.

So, people are really bad at making decisions, and a computer can conceivably be better than “very bad.” And that is in fact true. Artificial intelligence is already in many ways better at making decisions than humans. It can be simple check-lists made by humans for job applicants or it can be complex self-learning systems that dig thru large quantities of existing information.

Humans have presently two very powerful techniques for deling with bad decision making. The first is democracy. When individuals make mistakes, averaging the responses of many individuals has the potential to erase the impact of those mistakes. That is of course not a given; if you ask 1 or 1000 PSV fans of PSV’s chances of winning a game, you will most likely still get a gross over-estimation of their chances. But statistics, and their application in polling companies, has methods to increase the chances of erasing errors. Experiments indeed show that if students are tasked to judge winners of sports, they do a pretty mediocre job. If you tally up their predictions, you get a prediction that not only beats the worst or average student, but even outperforms the best.

The second approach it improve decision making is the exact opposite of democracy: it’s exploiting that correct decisions are not democratic. A classic problem is “a ball and a bat are together €1.10; the bat is €1 more expensive than the ball, how much is the ball?” Most people will have as immediate answer “€0.10;” even people who knows maths will often have this as their first answer and need to think about it. People who know the problem will know the answer is €0.05; if the ball were €0.10, the bat would be €1.10 and the total would be €1.20. The point is that most people would go with (and experiments demonstrate this) their first impression and answer €0.10. The democratic answer would be €0.10 (or just under if a very low percentage suggested the correct answer of €0.05 and we averaged the answers. In a group, it would only take one person to either think the problem thru or know the right answer to easily convince the rest by just mentioning that €0.10 + €1.10 = €1.20 while €0.05 + €1.05 = €1.10. The truth is not democratic, and sometimes people find it much easier to accept the right answer once presented than they do arriving at it themselves.

Artificial intelligence can in principle make use of averaging techniques, giving it much of the same power as democracy. It can, at least for some classes of decisions, be taught to recognize the “correct” answers from the wrong. For a simple computation it is easy – it doesn’t even need to weigh in on suggestions, but can outright compute the right answer. For some slightly more complex problems, knows as the NP-complete problems in computer science, it cannot necessarily compute the right answer, but it can recognize it if it sees it (and can make very good guesses).

However, in some situations, computers or artificial intelligences are not merely observing and reacting to the world around them, they are directly interacting with them. What one human does can in most cases be viewed as merely reacting to the world. Most people will have no measurable impact on the world at large, and one person using an artificial intelligence will not have any impact on the world. However, a strength of artificial intelligence is that everybody who uses it will benefit as they will be able to make better decisions, so there is a strong incentive for everybody to use artificial intelligence once available, and once we do that, we all start reacting in the same way. The averages of our decisions become less like an informed poll by a polling company with at least some rudimentary understanding of statistics and independent variables, and more like asking 5 of your football buddies about what they expect the result of tonight’s game to be.

We already see this impact; when GPS navigation was first introduced, it allowed drivers to take shorter, faster routes. They benefited from rudimentary artificial intelligence (a vaguely clever storage paradigm of the map and a simple A* shortest path algorithm). However as more people started using it, some roads often preferred by the navigation became more congested and other secondary roads would in fact be faster. GPS units improved and started including congestion information, but that would only be reactive and divert drivers away from an already existing queue, leaving the ones already caught with a much slower route.

We already see this impact; when GPS navigation was first introduced, it allowed drivers to take shorter, faster routes. They benefited from rudimentary artificial intelligence (a vaguely clever storage paradigm of the map and a simple A* shortest path algorithm). However as more people started using it, some roads often preferred by the navigation became more congested and other secondary roads would in fact be faster. GPS units improved and started including congestion information, but that would only be reactive and divert drivers away from an already existing queue, leaving the ones already caught with a much slower route.

This behavior is not unique to computers; people exhibit the same behavior. Some (idiot) investors like to talk about how a stock will meet resistance as it gets close to one of its Bollinger bands or some other limit (the highest/lowest it has ever been, has been in a week/month/year/decade, or a particularly nice number). Stocks have no such preference whatsoever. In a perfect market, the price would fluctuate purely depending on bids/asks. Whenever I purchase a stock, I almost immediately put it up for sale again. I simply add 7-10%, which is my expected short-term gain on a stock, and put it up for sale for that amount. If it gets sold, great, I make 7-10%, and if not, I re-evaluate my options. May others do the same; some, especially those who deal with geared investments, also add a stop-loss sale, so if the stock loses more than 10-25% (or whatever), it is sold to prevent the loss from getting larger. Rather than putting the stock for sale at 179.15, most people will round that off to 180. Or 200. Many people purchase stocks using the same technique: look at the current price, deduct a bit to get a “good price” and put in a purchase order. Round it off to something nice. For this reason, there is often many more bids/asks at “nice” numbers, so a stock has a hard time breaking that barrier, and once it does, it gets into a zone with far few orders and can fluctuate more freely. This works for anything some sperging investor with a way too large hard-on for technical analysis will consider a “nice” value. And this natural tendency will only be exaggerated once people are aware of it, because if a stock “breaks thru” 180 and people believe that this fact means the sky is the limit, this becomes self-reinforcing, because it will psychologically have large value because of perceived increased future potential. The prediction becomes self-fulfilling as more investors have access to the same instruments for technical analysis.

And this is the problem: as artificial intelligences become better and better, more will benefit from using them. This means our decisions will be made by far fewer entities, and our thoughts turn into mono-cultures. Mono-cultures are feared in agriculture, because while the crop may be stronger (smarter) seen as one, it becomes vulnerable to the same tricks. Bananas are largely a mono-culture, and whenever there’s a disease, there’s always great feat that it will spread and entirely kill off the entire banana harvest and force us to use a less tasty or resilient (and hence cheap) species. This has in fact already happened once, and the species of banana we enjoy today is not as tasty as the previous generation.

As it stands today, it is likely that we’ll end up with just a handful of artificial intelligences: Google has one, Apple has one, Amazon is building one, Microsoft in their recent me-too fashion has one, and there’s a couple less relevant research ones. In fact, just a day or two ago, the news broke that an AI alliance has been formed, which turns this into just two competitors: Apple and the rest. There has been some quipping in the open source communities about whether it would even be possible to make an independent artificial intelligence. Making the code is relatively easy; a lot is already available and building on 20-30 years old techniques. Building the hardware platform is harder, but still doable. However, feeding it enough data to gain any real usability is a huge challenge. Maybe these will not be the winners, but it is very likely that at least 80% of the market will be served by only a handful artificial intelligences in 20 years. And even if there are more, if they are trained using the same algorithms and data, they are not really different even if they have different owners.

We have already had a couple tastes of what thought monocultures cause. With globalization, we know more about what is happening in the world and share much more experience. We are therefore already more likely to make the same decisions or mistakes. Media is centralizing; most news come from just a handful of news agencies. To witness the impact of this, just consider presidential candidates. In the west it is entirely inconceivable that anybody in Russia would vote for Putin, yet he just won an election with over 50% of the votes. Our media picture makes it inconceivable to vote for him, yet the Russian media picture makes it meaningful for half to population to do so. In Europe very few can understand why anybody would vote for Trump, yet he is running pretty much head-to-head with Hillary. It’s not necessarily the case that one of the media pictures is right and all are wrong; it’s a case of them all being wrong in various ways and feeding and reinforcing opinions masquerading them as facts.

Simple artificial intelligences are already running parts of our lives. Most stock trading (by value and number) is done by computers these days. There’s a race to get the lowest trading times, because getting information milliseconds before others, allows you to make trading decisions based on information others’ don’t have yet, and therefore to make money. The same algorithms look at the prices and can make decisions based on this, including aforementioned selling instructions. If such algorithms have been taught that stock markets have magical boundaries and that going above or below one of these means gain/loss, they would act on it. So, if a stocks loses an unusual amount for some reason. It might be a large stock-holder selling out (like what happened to Lehmann Brothers and what might be happening to Deutsche Bank right now), some stop-loss actions might get triggered, causing prices to fall further. This might start a feed-back loop causing other triggers, and further drop. This is not a theoretical issue; this has happened. This is what happened during the Lehman crash, it happened (the other way around) when the Swiss let their currency flow freely, it has happened several times this year in China due to devaluations). It is so common, even, that most stock trades have emergency switches that prevent a stock/the entire index from falling/rising more than some given percentage.

A similar feedback that caused the financial bubble to burst, caused it to build up: it was possible and safe to make money on credit default swaps, so they were very popular. This made them even more profitable and therefore popular, so it was necessary to make more. The safe mortgages were bundled with slightly less safe ones, then less and less safe, until people essentially traded insurances that people with subprime mortgages would pay them back as safe papers. As long as it kept going, it really was; people with subprime mortgages would never have to pay them back, because the cheap and abundant debt made housing prices rise, which made it easy to refinance your mortgage whenever you had problems.

A similar feedback that caused the financial bubble to burst, caused it to build up: it was possible and safe to make money on credit default swaps, so they were very popular. This made them even more profitable and therefore popular, so it was necessary to make more. The safe mortgages were bundled with slightly less safe ones, then less and less safe, until people essentially traded insurances that people with subprime mortgages would pay them back as safe papers. As long as it kept going, it really was; people with subprime mortgages would never have to pay them back, because the cheap and abundant debt made housing prices rise, which made it easy to refinance your mortgage whenever you had problems.

Feedback-loops like this happen in a lot of automated procedures; this is why your computer’s nightly tasks happen with a randomized delay to prevent all computers in the world from starting working at the same time. This is why network gear has a randomized behavior in case of errors. Perfectly optimizing algorithms just have a tendency towards devastating feedback loops.

Artificial intelligences can have all kinds of protections built in, but when most of us behave the same, we are much more prone to such feedback loops, and the only way to break them is to introduce erroneous behavior. It is easy to claim the subprime crisis was created by greedy bankers, but that is simply not true. It was created by anybody who had a mortgage and anybody who had savings.

It might be easy to say we just all have to be less greedy, but are you going to be first in line to get slightly less safe car because it might statistically safe lives? Because that’s a real thing; automatic cars already struggle with the dilemmas of how to behave morally ambiguous situations: crash the car over the cliff killing everybody inside, or hit an innocent cyclist? Hit an old woman or a young buy at an intersection? Can you really truthfully say that you’d accept a slightly higher risk of your family suffering a horrible death in a car crash on the off chance of statistically saving a criminal 2 years down the line? Or are you going to be honest and get the one that would plow thru a kindergarten to save you from a mild inconvenience?

It might be easy to say we just all have to be less greedy, but are you going to be first in line to get slightly less safe car because it might statistically safe lives? Because that’s a real thing; automatic cars already struggle with the dilemmas of how to behave morally ambiguous situations: crash the car over the cliff killing everybody inside, or hit an innocent cyclist? Hit an old woman or a young buy at an intersection? Can you really truthfully say that you’d accept a slightly higher risk of your family suffering a horrible death in a car crash on the off chance of statistically saving a criminal 2 years down the line? Or are you going to be honest and get the one that would plow thru a kindergarten to save you from a mild inconvenience?

When we ask the artificial intelligences to take over much of our routine thinking, we need to make sure that the huge monocultures of thought we unleash doesn’t result in feedback loops. And we need to be aware that if we do this by introducing erratic and suboptimal behavior to break the loop, it will always be possible for an unscrupulous user to disable this to get the full optimized behavior – if one person does it, it can’t hurt anybody, right? – and then the next will as well…

Good points. It explains the importance of (bio/tech)diversity to obtain a stable system.

Biological evolution has created this diversity thanks to the long time available. Technological evolution may be going to fast to allow for this diversity to emerge.

I’m not so sure the speed of the evolution is the major problem, but rather that we only have 3 individuals: Amazon, Apple, Google (plus or minus a couple). How can we have diversity if we all rely on just 3 individuals?

On the one hand, we currently see people just disregarding their GPS because they know a certain road will be busy, but on the other hand we see modern GPSes rely on congestion information during computation as well.

But if all autonomic cars in 10 years will be clones of one of just 3 individuals, all the time in the world will have a hard time to lead to diversity unless we build into the systems that they should not make individual optimizations, but global ones – even if that is locally sub-optimal.