According to a tired cliche, the victors write history. Similarly, classifying an event as a protest, a coup, or a riot also depends on one’s perspective. But why don’t we try walking a mile in somebody else’s shoes for once…

Last night, tens or hundreds of thousands of Trump supporters stormed the Congress and interrupted the rightful election of Biden in attempt to stage a coup to keep Trump in power despite him losing the election, causing material damage, damaging trust in democracy, and even leading to casualties. Half a year ago, people rightfully stood up against racially motivated police violence in attempt to instil justice and equality.

Half a year ago, anarchist rioters decided to ignore pandemic warnings and took to street to burn down mom and pop stores under the banner of domestic terrorist group Antifa and the guise of Black Lives Matter to fight the people keeping us safe. Yesterday, patriots took to the street in a peaceful protest to defend democracy against obvious voter fraud.

Those are two different perspectives of the same events. They are based on descriptions I’ve seen around the internet, though they obviously come from wildly different parts of the internet. You most likely agreed with the one description, while the other was obvious propaganda a or “fake news.”

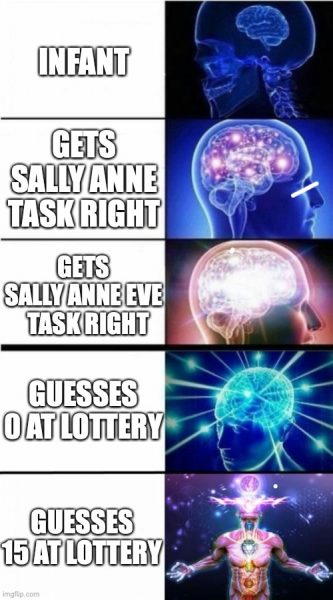

Psychology has a notion called “theory of mind.” Theory of mind is the ability to reason that other people have a different perspective than yourself. It is most often illustrated by the “Sally Anne task,” a psychological experiment wherein the subject sees two dolls, Sally and Anne. The experimenter has Sally put an item in a box with Anne watching. Then Anne “leaves,” after which Sally removed the item from the box and hides it behind the curtains. Anne re-enters, and the experimenter asks the subject where Anne will look for the item. Most people reading this, will suggest Anne would look in a box, but that is not universal: children will suggest looking behind the curtain until around age 4-6. Children do not have theory of mind and cannot grasp that Anne has a different model of the world (the item is is in the box according to what she saw) than the subject (Sally moved the item behind the curtains). This can be lifted to the meta-level; for example, add a third doll, Eve, observing the regular Sally Anne task, make Eve leave and let Sally put the item back in the box. Now the question is where will Eve say Anne will look for the item? Now, we’re no longer reasoning about other people’s models of the world, but about other people’s models of other people’s models of the world.

This is similar to a classical game: there’s a “lottery.” Participants each give an amount between 0 and 100, and the person closest to ⅔ of the average of all guesses wins that amount. What is the best guess? If people guess at random, the average is 50, and ⅔ of that is 33⅓, so that would be our guess. Except… if other people realize this, the average woudl be 33⅓, so the correct guess is 22.22. …but if people realize this, the right guess is 14.81, etc. We can continue this line of reasoning, and in the end, the right guess would be 0. Except not all people would realize the answer is not 33⅓. And not all would realize the guess isn’t 22.22 or 14.81. And some would realize that some people would realize it just like we did. Thus, what seems like a simple math puzzle is really one about psychology: how many levels of theories do people exhibit? Practical experiments show that people tend up with correct values of 15-20. But more interesting, we can follow the levels of theory of mind here as well. A guess of 33⅓ suggests no theory of mind applied (but good ability to read and execute Math problems), a guess of 22.22 a single level (Sally Anne task level) and 14.81 is theory of mind at the meta level (Sally Anne Eve task level). Guessing 0 is at another meta level: now we not only realize that people think about other people thinking but also that this can go on indefinitely (this is where most introductory psychology classes are). Guessing 15 is another level of meta: now, we no longer reason about people but also about people reasoning. You and I, dear reader, are of course the next level: we not only reason about people reasoning, but also at the level that reasoning about people reasoning continues, and that this adds another level of meta, and that these levels of meta can continue indefinitely, leading to even more complex and removed from reality levels of thinking about thinking instead of getting done. Damn, we’re smart. If you’re into numbers, this is also similar to how infinite cardinalities are created using powersets or large finite numbers using the Ackermann function/Knuth arrows.

Similar to theory of mind, psychology also has the concept of “empathy.” It means roughly the same as in common use: it’s theory of mind but for feelings: it’s about feeling what other people feel. Sometimes theory of mind is also called cognitive empathy and what I call empathy is called affective empathy to distinguish it. Empathy and theory of mind are not universal, but developed during age. Also, not everybody develop them to the same degree. For example, people of the autism spectrum often has normal ability to perform theory of mind but lowered ability for empathy, while people with psychopathic tendencies tend to have lower empathy. This is wildly simplified, contested, and using old language in attempt to get the point across, so don’t get stuck on the details: theory of mind and empathy are not universal and people experience them at different levels.

We see the difficulty of theory of mind in many places. For example, outgroup homogenity bias. We think that people we disagree as a single mostly uniform, homogenous group, while our own group is more nuanced and heterogenous. This is in part because we understand the thought process of the ingroup: we are there and get our own thoughts, we see there are people inside our group that we disagree with on various points. People outside the group are all caught by “we don’t agree with them,” so they all think the same for all we care. We think we understand the thought process of the outgroup, but conflate it with our own thoughts and subconsciously over-simplify things.

Just like there are theory of mind and empathy to deal with thinking about and feeling other peoples thoughts and feelings, I believe we also need to extend this with a “theory of knowledge/belief/reasoning.” It’s possible somebody already did, but this is not an academic essay but just a blog post, so I’d be damned if I’m doing a literature search to settle that. We need to be able to follow other people’s arguments from their base of knowledge to really understand them.

I think “theory of belief” (let’s call it that) is extremely difficult. It’s just supremely difficult to sidestep our own knowledge and reason from another person’s perspective, just like we saw for the outgroup homogenity bias. This is likely related to cognitive dissonance. Our brains really dislike holding two contradicting points of view simultaneously, to the point that we see a whole slew of effects rationalising our views to resolve the dissonance. Consider the rotating ballerina to the left; is she rotating clockwise or counter-clockwise. Most people see her rotating in one way (it has nothing to do with left/right brain halves or anything like that as often proposed), but it is very hard to see her spin in the “other” direction: we know physically she can only rotate in one direction, so our brain resolves the dissonance of the lacking depth information by making her rotate in one of the two possible directions. Some people accidentally or even consciously see her changing directions. Being able to see the ballerina spin in both directions is similar to (and may even be correlated to) being able to suspend cognitive dissonance or at least one version of realty, and see things from multiple points of view. I’ve always been able to do it to some extent, but amusingly didn’t realize this was not universal until some years ago. Like theory of mind and empathy, I believe that theory of belief is non-universal but is something we (can) learn.

So, let’s consider yesterday’s protests. Was it caused by “insane Trump fans willing to do whatever Fox News and Trump’s Twitter tells them to” or “patriots standing up for democracy faced with election fraud”? Now set aside your preconceptions about what is true. Would you also protest (or support protesting) if there really, genuinely was election fraud and the wrong candidate was about the get inargued? That can be really hard to imagine, because our mind keeps insisting “but there wasn’t.” But what if there was. It’s not a belief, it’s certain knowledge. A trick I find useful is to swap the roles. What if Trump was about to become president for another 4 years, despite Biden winning the election? Would you feel that was fair? Would you be willing to protest that or at least sympathise with people that did if this were the case? Is occupying the Congress without use of weapons or violence to protest the illegal inauguration of Trump a reasonable measurement? Try to really feel the scenario.

That scenario is literally what people went thru yesterday. They do not “believe” there was election fraud. They “know” it. Just as certain as you “know” that there wasn’t. We “know” things because we see our world-view and reasoning, just like we see our ingroup, as nuanced and based on sound arguments. Others cannot “know” things we “know” to be false, so they must just be (incorrect) “beliefs” rather than “knowledge,” just like an outgroup is homogenous. “Election fraud” and “no election fraud” cannot exist simultaneously in a consistent universe, but “I/they believe there was election fraud” and “they/I believe there was no election fraud” can. Our knowledge is not based on cold logical arguments, but a product of our entire lives and current situation. While truth (sometimes) is, knowledge is not absolute. Consider how many wine-aunt minion memes and Alex Jones videos it would take to convince you that there genuinely was election fraud? 2? 5? 42? more? I’m guessing the answer is that no amount of Infowars videos would ever convince you. Now consider how many CNN articles it would take to convince somebody normally getting their news from Fox (not News, but The Simpsons) and the aluminum-wearing soy pill salesman. Your arguments carry no weight to them, just like their arguments are useless to you. They do not “believe” that there was election fraud any more than you “believe” Biden won. They “know” with 100% certainty that the vote was rigged and Biden is illegally assuming power. Knowledge vs belief has nothing to do with veracity, but purely with point of view: I know, they believe.

Our knowledge is not based on information, it is based on our feelings, experiences, and the information we choose to take in. And the information we choose to take in is based on our knowledge and feelings. That’s the crux of confirmation bias and is also related to cognitive dissonance: proof against our beliefs are simply uncomfortable. We need to use this in two ways: we need to use it to get inside the minds of others and see their perspective, and we need to use it to re-evaluate our own knowledge. We do not have “knowledge” while they have “beliefs,” and we need to realize that sometimes we are in the wrong. Also when we know we are right, we might be wrong, and this is largely unrelated to how much we feel certain something is true. How come it is so easy to see when Russian newspapers are dissiminating propaganda, yet we never see it in our own newspapers? Why did people in the UK see such a different story about Brexit compared to people in the EU? While contradicting beliefs can easily coexist in a consistent universe, contradicting realities cannot, so one of us has to be wrong (only talking about objective, knowable facts here, some things are judgements which, while interesting, does not matter to the present discussion). And what is the probability that it is always the other person? Sometimes we, too, are wrong, and that also happens when it is not about a belief but certain knowledge.

Just opening the door to being wrong does not mean that both or all possibilities are true with the same probability. I genuinely believe the Russian newspapers are less truthful than the best Western newspapers (but my Cyrillic is sketchy at best, so I’ve got some outgroup homogenity bias going there too). I believe there was no election fraud in the US election (there was most likely small cases here and there but nothing coordinated and nothing that made a difference or was different from 2016 when Trump was elected). I believe that evolution is true while intelligent design is not. I believe abortion should be a woman’s choice. I believe all races are equal, and while I believe people are born with different abilities, they should be given equal opportunities with a slight bias towards also equalizing outcomes. I am also aware these are all beliefs and that others may disagree on certain points. While these beliefs are very strong, I also know they are just that. That means I try to stay open for other beliefs and most importantly “theory of belief” my way into other people’s minds. That does not mean I view “nazism” as equally valid to “races are equal,” nor do I believe there’s a 50/50 chance between evolution and intelligent design, but I do realize that “giving the mother a choice” is fundamentally at odds with “humanity happens at conception and murder is wrong,” and that people against abortion are not doing it entirely out of spite and evil.

I think I started considering this around 2010 when I moved abroad. In Denmark, I’d hang out with my ingroup and we’d always be the smartest people in the room. After moving away, I’m starting to see a lot of things from the outside. I’m no longer following Danish politics as an insider but mostly as an outsider (and same with Dutch). I’m not allowed to be involved in either place (as expat I cannot vote for national governments in either place), so I’m starting to see cracks in the arguments of not only the people I disagree with, but also the people I (used to) agree with. It may also in part be “getting older.” I started argumenting using “devil’s advocate” arguments, honestly not to troll, but to see things from the other side. I did that both to people I agreed with and people I disagreed with. I’m getting that people thought I really held those beliefs 100% instead of just arguing according to a knowledge base I didn’t necessarily agree with myself. People started considering me as a outgroup member and stopped seeing individual arguments, but instead started arguing with the ghost of an opponent they had in their minds. If we ignore this is an assholish way to argue (it no longer matters whether you win or lose, for one), I now see it is also due to differing levels of theory of belief. This is also a large part of why I started studying psychology: to understand why we do dumb things.

That is a large part of my hope with this post: can’t we try looking at things from other people’s perspectives? How are the BLM protests similar to the democracy protests of yesterday? I’d say in most ways. Sure, there are technical details where they differ, but that’s the point! Why do we insist on focusing on the differences instead of the similarities? People went out protesting for what they believed in. Some behaved badly, most people just showed their dissent. Some were at odds with police, some broke into places they should not have been, while others listened to guidance.

It’s not necessarily easy to equate two things with different emotional value. There’s a great quote which paraphrased goes “knowing is not half the battle, nor is knowing that knowing isn’t half the battle.” It refers to the G.I. Joe fallacy, based on some kids show that ended with “knowing is half the battle.” It turns out that in many and significant ways knwoing something isn’t half the battle of doing/completing it. Knowing how to construct a bridge is not half the work of building one. Understanding that the BLM protests are essentially the same as yesterday’s democracy protests is not the same as feeling it. No matter how much I rationally argue the point, I cannot help my brain interrupting with “but they are trying to get Trump reinstated even though he didn’t win” vs “they wanted polite to stop killing people with brown skin.” My cognitive dissonance keeps making one of them good while the other is wrong. Everybody sees themselves as the only sane person in traffic; other people are either too careful, slowing down everybody else, or too aggressive, putting others at risk. I have a view of myself as law-abiding, so I don’t break the laws, but sometimes I cross a red light if there’s not other traffic around. My cognitive dissonance has to resolve the contradiction between “I’m law-abiding” and “I cross at red with nobody nearby,” and decides “crossing at red with nobody nearby” is not really breaking the law, the law is just a bit silly there and really more of a loose guidance. So, when I get to a red light and there’s nobody around, I just cross. If there’s others around, I stop. Now, on a bike the problem with stopping for red is the stopping part; waiting for 10 or 60 seconds makes virtually no difference (unless I’m in a hurry). So, if I’ve already stopped I just remain stopped until the light changes. Now, if I’ve stopped at red due to traffic, the traffic disappears, and somebody else comes up and crosses for red, I cannot help but feeling they are breaking the law. I’ve already stopped and I’m a law-abiding citizen, so somebody else crossing must be doing something wrong. Even though I would likely have done the same has I arrived later when traffic was gone. The thing is, I know I would do this. I know I’d feel this. Yet, I still do. Knowing is not half the battle. And even knowing that knowing isn’t half the battle isn’t half the battle to resolve it either, though I now kind-of laugh at myself when it happens because I know the feeling is irrational, and know that I know that etc. Other people are not always bad in traffic, they just had different experiences (no traffic when they got to the light) or slightly different norms (while I don’t start crossing a red when I’ve already stopped other might, or they may have different thresholds for “no others around”). I also realize the double-standard of this post together with my disdain for anti-vaxxers and people who break quarantine during a pandemic – knowing isn’t half the battle, nor is knowing that knowing isn’t half the battle. But it is a start.

The reason we need to better understand other people’s beliefs is that only then can we stop othering them. And only then can we start understanding each other. It has been shown that it is much easier to change people’s actions/beliefs than their identity/knowledge. Our identity is part of our selves, and viewed as unchangeable (though we change and just don’t notice). Changing our identity may mean we lose our social circle or standing, so it is very risky, and changing something tied to an identity gets in conflict with cognitive dissonance (“I’m a Trump voter, but Trump voters dislike brown people, but Harry is a fine person, ergo Harry isn’t a brown person but different somehow”). Doing this really, genuinely helps is moving minds. Minds of people we disagree with, and our own. We just might not notice it, since movements often are smaller than a total, instant and unrealistic “American History X” flip, but instead just small pushes we don’t notice in ourselves or changes in others that get abstracted away by outgroup homogenity. I consciously try not saying “I am” something, but instead that “I do” or “I believe” something. I am not a vegetarian, I just don’t eat meat (except sometimes I do). I am not a Java developer, I just code in Java (except sometimes I code in other languages). I am not a project manager, I just happen to do a suspiciously increasing amount of project management. I am a Britney fan, though.

I believe this is important to do ourselves to not get locked into beliefs that should be changeable, and it is is also important to do it for others. Don’t view people as “Trump voters” but as “people who voted for Trump” or “people protesting for democracy.” Because “people who protested for democracy” are much more similar to “people who protested for racial equality.” The polarisation of society is less about the (lying, social or otherwise) media and more about us believing polarization is happening. It’s fine not to agree that the vote was rigged, but otherwise consider the belief process leading to the actions without condemning the actions. Let’s avoid labelling people and look at their actions and beliefs, while we do the same for ourselves. This is not about changing the minds of people we disagree with, but about changing our own perception – if enough people do that, it just might hit somebody we would otherwise disagree with, and wouldn’t that just be nice.

😉 Hi Michael, spændende læsning