It’s not a question, it’s a statement: I’ll describe exactly what’s wrong with them and my solution, nay, the solution to the problems. This is not some thinly veiled racist protectionistic “the problem is really outsourcing” manifesto, but rather a description of what is wrong with most pieces of software for running service desks.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve worked with numerous ticketing systems. They are all bad. Jira Servicedesk? Sucks. ServiceNow? Hitler in web-app form. Remedy? Bubonic plaque but with Internet Explorer 6 (the bad one). They all require tons of configuration and suffer from not supporting working according to processes, but hindering it. On top of that, they constitute a secondary ticketing system (or tertiary in one case) doubling the fun paper-work part of the job. The tools also seemed to be too stuck in their ways; they would support ITIL, but not be flexible about it. Sometimes, a ticket is logged incorrectly, and it is largely impossible to get an incident recategorized as a change.

I had high hopes when we were evaluating solutions: there was so many and some of them would have to not suck. Seems they all focused on being configurable to do everything and as a consequence monsters to use. We looked into FreshDesk, ZenDesk and one or more additional products. We settled on Jira Servicedesk, because we (collectively, not including myself) liked Jira the ticketing system. I had the naive hope that being made by the same people, it would have nice integration with that (so I would be able to turn an SD ticket into a developer story easily and the like).

I like simple ticketing systems. To the point that back in the early 2000s, I built my own instead of bothering with BugZilla, which was the big one back then. Building my own allowed me to ad features hitherto impossible, such as allowing users to create tickets without an account, and to generate release notes based on tickets.

One simple ticketing system I like is the one in Gitlab; it is relatively simple, allows scrum-like processes, but is not religious about it, and it is integrated into Gitlab. That means tickets know of releases, milestones, tags, branches and can be linked easily. I know that Gitlab themselves use it as a service desk (and they even sell a professional version which claims to include a service desk). As good it is for developers, it is not good for end-users, though: it has too many options.

So how about this: build a simple web-UI on top of the Gitlab ticketing system allowing customers to register tickets. Allow developers to do anything, but set up simple ITIL (-like) processes to assist them. Leverage the existing ticketing system instead of adding something new. Yeah, that’s the stuff!

So I did; I’m working on a single PoC showing how to fix the world (and service desk software, more the latter than the former). So, here’s what we do:

Gitlab supports issue templates. That’s neat if you’re into that sort of thing. Which we are. We simply set up a template for each kind of ticket; in ITIL terms that would include something like Incident, Change, Problem, Request.

We can even set up multiple templates for each kind of ticket. That means that we can create a generic Change template, but also one for “Create account” or “Bugfix,” simple standard changes which can skip the analysis phase and comes with a pre-approved budget.

Issues in Gitlab supports quick actions, which are just slash commands you can enter into issues or issue comments. That’s pretty much perfect for us because they allow us to add things like time estimates, due dates and labels ()just tags but with another name) to issues. That means that a “bugfix” change can embed a quick action for approving spending, say, 4 hours or to put in an SLA.

We can also use labels for fields where nothing quite matches in Gitlab. For example, Gitlab just has one type of issue, so we cannot easily distinguish an issue representing a change from one representing an incident, for example. But with labels we can: add a label “type:change” to changes and one “type:incident” to incidents. That makes it easy to list all changes but also to move a ticket from one process to another.

By using structured names like type:change and type:incident instead of just change and incident, we can automatically gather all tags of the appropriate type. That means, our servicedesk application doesn’t have to know about ticket processes, it just has to recognize the appropriate labels.

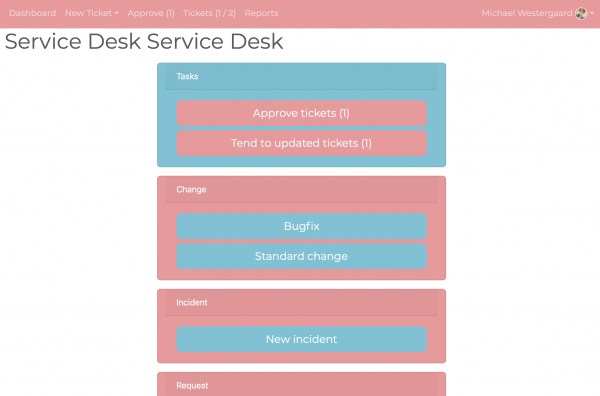

So, this is what we do: we fetch all issue templates from the repository and present them to the user using a standard portal that looks like all other service desks out there:

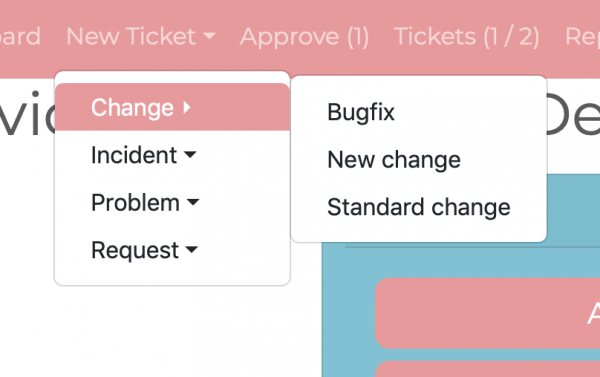

We have a pink box for each type of ticket, and actions for each template. The ticket types are scraped directly from the templates as are the names. We only show the most important templates on the front page and generate a menu with all the templates:

Here, we see there’s actually a third change template in the system and an entire category (problem) not listed on the portal front page. This is simply controlled using another label.

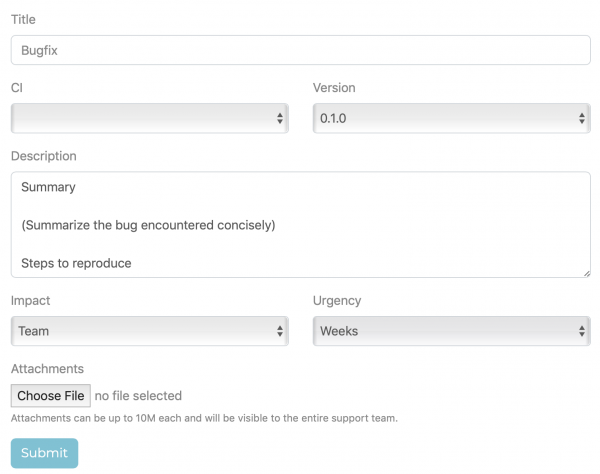

When a user clicks on one of the buttons (or selects from the menu), they are greeted with a very standard submit ticket screen:

The title and description come directly from the template. The version is calculated based on project tags (here we assume, that a git tag is created in the repository for each release). The impact and urgency are just more labels, but since we can control that from templates, different tickets can have different default values and can even be locked to the default (so a standard bugfix like this one will have a fixed urgency; if it needs to be handled faster, the template cannot be used).

I’m also proud of the ticket prioritization; many ticketing systems allow customers to select a priority of high/medium/low or P1-P3 or something of the sort. Of course, even the most minute textual change on an obscure help-page that has not been opened since the happy 90s seems like the most important to the person dealing with it right now, but if everything is of high priority, nothing is. Instead, I allow customers to select the impact (from the entire company to a single person) and the time horizon the issue needs to be fixed on, not on an abstract scale but based on a scale of months-hours.

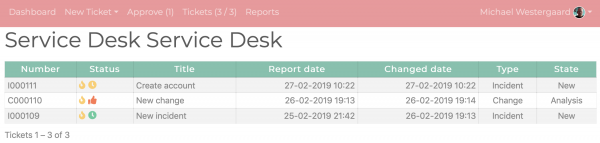

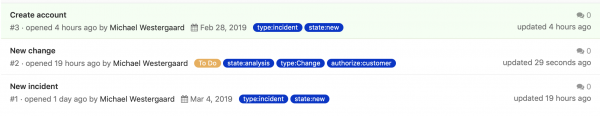

We can of course also list issues in the system:

Most of the fields should be clear; the state is just another structured label, so the process can flow thru any number of template-defined states. The report and change date are just as maintained for issues in Gitlab and the issue number is generated based on the Gitlab issue id and ticket type so they look like “proper” ticket numbers.

There is also a status column giving quick insight to the status of the ticket; the yellow flame means the ticket has been updated recently; here they all have as I’ve set them up for testing. The red thumb up means the ticket is blocked, waiting for approval from the customer (another label). The yellow and green clocks indicate that the tickets have a due date (the change here does not) and that it is getting close (in the case of the yellow clock – there’s also a red one indicating it has bee passed).

The tickets, of course, show up in the regular issues view in Gitlab, where we can also see the labels applied (they can be color coded, but I’ve not bothered yet):

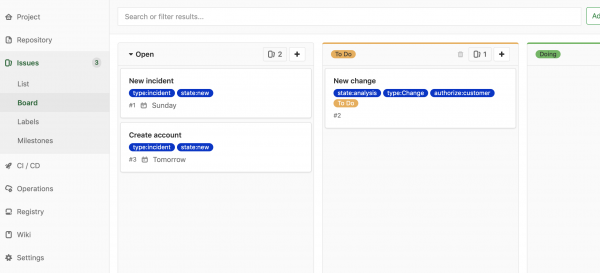

We can view them in the issue board view to get a more scrum-like view:

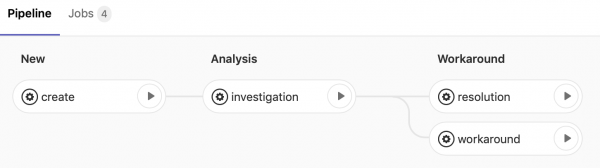

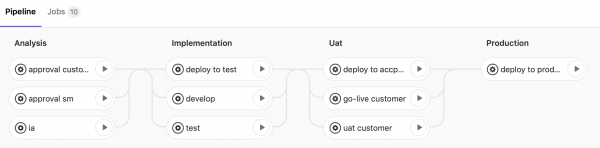

Of course, we have to handle the process flows as well. Instead of rolling my own (though I did look a bit a Spring State Machine, but couldn’t find a simple way to load a state-machine from a file so gave up), I thought why not just rely on Gitlab’s CI/CD solution, which supports describing and running tasks according to a process.

I’ve not worked out all the details yet, but have set up concept pipelines for simple incident and change processes:

The tasks are available and viewable from Gitlab directly, so developers can trigger them. I need to set them up so they can communicate with the service desk application to check if progressing is allowed and use a simple language to make mutations (executing quick actions).

I plan to add other obligations as labels. This can include requiring approvals from various parties (an early version is already implemented), requiring various documents, etc. Satisfying a requirement corresponds to changing a label; I’m thinking something like document:requirements to indicate that a requirements document is needed; when it is added, the label can be removed and the ticket proceeds. Adding and removing labels is logged in the ticket, so there’s always an audit trail of who did what.

The same can be done for state transitions: add a state:analysis move the ticket to the analysis phase and have the application trigger the corresponding CI jobs to validate the transition. Or trigger them from the UI? I’m not entirely certain yet.

Since everything is versioned, it is possible to update the ticket process, yet old tickets will run on the old version until they are complete. Same goes for templates.

Things get a bit fuzzier here, near the end; I’m still working on the PoC and haven’t fully detailed everything yet. I have a bunch of ideas I want to play with, including SLA reporting, adding an auditing daemon ensuring tickets run according to process, integrating with e-mail, time tracking and reporting, etc.