A couple of days (read 2 months) ago, I wrote why I believe Bitcoin is a bad investment. At the time, I promised to write about the technical shortcomings of Bitcoin. I did, and my browser crashed eating a large chunk of my post, and then I got busy with my studies again. I also actually looked at some of the implementation details of Bitcoin, and decided to write about them. This post is neither of those. I might still write them, but this time, we’ll look at 7 misconceptions about Bitcoin. Maybe 7? Fuck it, I can’t be bothered to write an outline and count them, and the blockchain is immutable so I cannot go back and fix it when I’m done writing ((Alternative Bitcoin joke: now there’s 6 misconceptions. Now there’s 8. 7 again. Now there’s 15.)).

Misconception 1: The Blockchain is Based on Cryptography and Mined using Complex Mathematics

The first misconception is not really that important. It just annoys me when people use the wrong words on the internet. They must be corrected! The conception is that Bitcoin is based on advanced cryptography and complex maths. Both are incorrect.

The first misconception is not really that important. It just annoys me when people use the wrong words on the internet. They must be corrected! The conception is that Bitcoin is based on advanced cryptography and complex maths. Both are incorrect.

Bitcoin doesn’t really use cryptography ((This is mostly true – the transactions in the blockchain do actually use simple public key encryption to sign transactions, but the blockchain itself doesn’t, and the whole mining shebang could be removed if it just used that for everything.)). It uses a cryptographic hash function, which despite its name is largely unrelated to cryptography. A cryptographic hash function is basically a hash function that is hard to reverse. A hash function is a bit like a fingerprint: no two electronic documents have the same hash value, just like no two persons have the same fingerprint. Both are incorrect but close enough. A cryptographic hash function is that but also hard to reverse. That’s a bit like how it is difficult to create another person with the same fingerprint as you. That’s useful in bitcoin, just like it is useful that you (and only you) can use your fingerprint to unlock your phone. It is unnecessarily complicated to unlock your phone by constructing another person with your fingerprint, and much easier to just beat you up and steal your finger. Nothing really to do with cryptography: it’s just based on electronic fingerprints.

As part of this, people tend to perpetuate that Bitcoin is mined by computers solving complex problems. That’s also not true. It’s instead solving silly problems an inconvenient number of times. The actual problem is computing the above cryptographic hash function a stupidly large number of times. This is done because the system makes some requirements on what the fingerprint must look like. Consider I am thinking of a number with 100 digits. I tell you you have to use a complicated procedure to come up with a number based on some input, and that number has to coincide with the number I’m thinking of on the last 3 digits. You cannot do the complicated procedure in reverse (like a cryptographic hash function cannot be reversed), so you just have to guess an input, do the procedure and hope it matches. There’s 1000 possibilities for the last 3 digits (000 – 999), so on average, you have to guess 500 times to get a number that matches. I want the procedure to take around 10 minutes, so if you can make around 1 guess a second, we’re good. If you guess faster, I just make it harder by saying the number must match on the last 4 digits or more. I can also reduce the complexity if guesses take longer. Bitcoin pretty much does exactly this: the value computed using the cryptographic hash function is a large number based on the block, and Bitcoin requires this number is less than a number decided, so it will on average take 10 minutes for everybody in the world to find a new block to add to the blockchain which has a hash value (the output of the cryptographic hash function) smaller than this number. There’s a reason for all this, but it is largely dumb and doesn’t detract from the fact that this is not a complex computation. This is guessing numbers and check they match a simple but artificially time-consuming rule.

The Bitcoin network could run on a SNES in a flooded basement and does not need the power equivalent of Denmark or the Netherlands. The useful part of the computation is relatively simple and requires virtually no computing power; the algorithm artificially inflates the difficulty because many people are helping in order to keep the production of new Bitcoin blocks at a near-constant speed. Again, there are reasons for this, but they are artificial and has nothing to do with complexity.

Misconception 2: Bitcoins Can be Subdivided Finer than Dollars or Euro (or Papiermarks or whichever currency)

Bitcoiners like to tell people how Bitcoins can be subdivided into Satoshis or 1/100,000,000 of a Bitcoin, so you can really make microtransactions. That’s all good and well. At the current exchange rate, which is somewhere between $10,000 and $20,000 to a Bitcoin, that means that Bitcoins can be subdivided into amounts of just $0.0001-0.0002 or just 1/100 of a cent. That’s much finer than what is possible using real money, right? Except no. There’s nothing preventing me from storing dollars at a much finer precision. In fact, banks do that already: when at the end of the year, I get a couple of penny-scrapings in interest, my bank has computed that on a daily basis over an entire year. It has accumulated this at a much higher precision rather than rounding to cents every day. There is nothing inherently preventing us from paying 1/1,000,000 of a dollar, except banks don’t do that because it’s too expensive to do the transaction. Just like it is for Bitcoin.

Bitcoiners like to tell people how Bitcoins can be subdivided into Satoshis or 1/100,000,000 of a Bitcoin, so you can really make microtransactions. That’s all good and well. At the current exchange rate, which is somewhere between $10,000 and $20,000 to a Bitcoin, that means that Bitcoins can be subdivided into amounts of just $0.0001-0.0002 or just 1/100 of a cent. That’s much finer than what is possible using real money, right? Except no. There’s nothing preventing me from storing dollars at a much finer precision. In fact, banks do that already: when at the end of the year, I get a couple of penny-scrapings in interest, my bank has computed that on a daily basis over an entire year. It has accumulated this at a much higher precision rather than rounding to cents every day. There is nothing inherently preventing us from paying 1/1,000,000 of a dollar, except banks don’t do that because it’s too expensive to do the transaction. Just like it is for Bitcoin.

Bitcoin is a bit different, though. It computes everything in these Satoshis or 1/100,000,000,000 of a Bitcoin, and cannot be subdivided. The protocol inherently forbids it: all transactions are done in a whole number of Satoshis. so, at best Bitcoin work as good/bad as real money and at a more realistic level, they are worse.

Misconception 3: No Inflation

Another point often perpetuated by Bitcoiners is that it has no inflation (as if that were a good thing). Where do they think the mined Bitcoins come from? That’s inflation right there. At this time, there are roughly 16.8 million Bitcoins in circulation (except around 1/4 are lost and the price depends heavily on this, but that’s a story for another day), and mining produces 12.5 new ones every roughly 10 minutes. That’s a total of 1,800 a day or 657,000 a year. That’s an inflation of around 4% right there. Most western countries have an inflation of around 2%.

Another point often perpetuated by Bitcoiners is that it has no inflation (as if that were a good thing). Where do they think the mined Bitcoins come from? That’s inflation right there. At this time, there are roughly 16.8 million Bitcoins in circulation (except around 1/4 are lost and the price depends heavily on this, but that’s a story for another day), and mining produces 12.5 new ones every roughly 10 minutes. That’s a total of 1,800 a day or 657,000 a year. That’s an inflation of around 4% right there. Most western countries have an inflation of around 2%.

Misconception 4: There Can Only Ever be a Fixed Number of Bitcoins

Sure, but that has to stop, right? Bitcoiners keep saying there’s a strict limit of the number of Bitcoins: there can only ever be 21,000,000 of them, so if we just assume there’s a fixed supply of 21,000,000 Bitcoins and mining just “finds” these instead of “making” them, then there’s no inflation. Well, that limit is a lie too. There’s nothing limiting the number of Bitcoins except convention. Instead of having a federal banking system with no personal interest in making money promising not to make too many, we have a small number of Bitcoin miners with a huge interest in making more Bitcoins (because they get themselves) promising not to make more than the 21 million of them.

Where does this misconception come from? Each Bitcoin “block” comes with a mining reward. It started out at 50 Bitcoins per block and is halved every 210,000 blocks (that’s chosen to be very close to every 4 years at one block every 10 minutes). That means there can in total be 210000 * 50 + 210000 * 50 / 2 + 210000 * 50 / 2 / 2 + 210000 * 50 / 2 / 2 / 2 + … = 210000 * 50 * (1+ 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + …). That parenthesis is what is known as the geometric series and can be proven to be equal to 2. That means there can be a total of 210000 * 50 * 2 = 21000000 bitcoins, regardless of how many blocks are added. That’s the only “check.” The way Bitcoins are awarded is that each block starts with a block saying that the person mining the block gets a reward of (currently) 12.5 Bitcoins (really 1250000000 Satoshis). Nothing in the protocol prevents the miner from just putting in 50 Bitcoins. Or 1000. Really. There’s no limit.

Where does this misconception come from? Each Bitcoin “block” comes with a mining reward. It started out at 50 Bitcoins per block and is halved every 210,000 blocks (that’s chosen to be very close to every 4 years at one block every 10 minutes). That means there can in total be 210000 * 50 + 210000 * 50 / 2 + 210000 * 50 / 2 / 2 + 210000 * 50 / 2 / 2 / 2 + … = 210000 * 50 * (1+ 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + …). That parenthesis is what is known as the geometric series and can be proven to be equal to 2. That means there can be a total of 210000 * 50 * 2 = 21000000 bitcoins, regardless of how many blocks are added. That’s the only “check.” The way Bitcoins are awarded is that each block starts with a block saying that the person mining the block gets a reward of (currently) 12.5 Bitcoins (really 1250000000 Satoshis). Nothing in the protocol prevents the miner from just putting in 50 Bitcoins. Or 1000. Really. There’s no limit.

The only caveat is that if the other participants in the network don’t accept the block, it is as if it were never mined, and the reward is lost. But all the other miners have a strong incentive to allow this sort of behavior: if they agree with the other miner that they mutually accept one another’s blocks with a 1000 Bitcoin reward, they themselves can get a much larger reward. In Bitcoin things are decided by majority votes, but majority is decided by hashing power, so the ones with most to gain from increasing the reward are the ones with the most votes. Sure, all the non-mining users can just stop accepting these blocks, but that means they either have to stop expecting transactions to be checked (transactions are checked by the miners) or make their network vulnerable to a hostile takeover. If 90% of the miners – by hashing power, not by numbers – decide to increase their reward, there will only be 10% of the network left. This 10% can be overtaken by the 90% mining blocks with large rewards. These miners can spend 1/9th of their power to inject garbage into the regular network (that’s what it takes to keep up with the genuine hashing power ), while continuing on mining their own network with larger rewards. I believe that’s a thing that might happen when the block reward is halved next time.

Every two weeks (really every 2016 blocks) there’s a difficulty adjustment, which means that either this trick stops working, or the now rogue miners can bring the Bitcoin network to a screeching halt for half a year, but the details are of a pretty technical nature and not too important here.

Alternatively, since bitcoins are lost from time to time when people forget their passwords or trash a harddisk, people might simply decide to make some more Bitcoins to make up for it.

All in all, there is no inherent limit on the number of Bitcoins. Instead, the limit is based on trust that those that have the most to win by not making more don’t make more. That sounds like something you can take straight to the bank!

Misconception 5: Bitcoins Exist

When people look at their Bitcoin wallet, they see a balance of, say, 7 Bitcoins and know they can just transfer them or part of them to somebody else. That’s useful as a metal mnemonic, but that is not actually what is happening. Instead, your Bitcoin wallet consists of transactions to you, and what you can do is spend these transactions. A transaction always have to spent in full. That sounds awfully complex and irritating, and that’s why wallets hide that from you, so you just have to think about sending Bitcoins to somebody else. Since we have the abstraction, why care about the distinction? Because of transaction fees.

When people look at their Bitcoin wallet, they see a balance of, say, 7 Bitcoins and know they can just transfer them or part of them to somebody else. That’s useful as a metal mnemonic, but that is not actually what is happening. Instead, your Bitcoin wallet consists of transactions to you, and what you can do is spend these transactions. A transaction always have to spent in full. That sounds awfully complex and irritating, and that’s why wallets hide that from you, so you just have to think about sending Bitcoins to somebody else. Since we have the abstraction, why care about the distinction? Because of transaction fees.

If Bitcoin had no transaction fees, the simplification would be fine, and you could just think of Bitcoins in your wallet as money in your bank account. Unfortunately, Bitcoin does have transaction fees. Popularly, you have to pay around $50 in transaction fees these days. In principle, that just means don’t transfer small amounts, right? Things are not so simple, though.

Actually, you have to pay for each byte of the transaction, because there can only be so many bytes in each block mined, and if your transaction takes up 200 bytes and pays $50 but two other people send transactions that are just 100 bytes but they each pay $30, the miner can get more money by taking the two transactions of 100 bytes at $30 each (for a total of 200 bytes and $60) than your single transaction for 200 bytes and $50. And depending on how you got your Bitcoins, a transaction might be more or less complex.

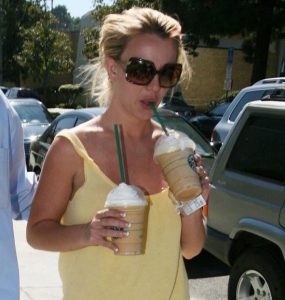

Let’s look at an analogy. When I’m paying cash, I might pay Britney $10 for a new album. I do that using a shiny $10 coin. Somebody else buys an album and pays $10 using another shiny coin $10 coin. Now, if Britney wants to spend $20 for a Strawberry Frappuccino or a Hibiscus Berry Tea at Starbucks, she cannot pay with a shiny $20 coin but has to pay with two $10 coins she received. It’s similar with Bitcoin: if I have received 1 Bitcoin from one place and 2 from another, I cannot just pay 3 Bitcoins but instead has to pay 1 + 2 bitcoins. The Bitcoin transactions are a bit like coins: when you give Bitcoins to somebody else, they cannot just be added together: the recipient has to use the coins you gave them in the first place.

Let’s look at an analogy. When I’m paying cash, I might pay Britney $10 for a new album. I do that using a shiny $10 coin. Somebody else buys an album and pays $10 using another shiny coin $10 coin. Now, if Britney wants to spend $20 for a Strawberry Frappuccino or a Hibiscus Berry Tea at Starbucks, she cannot pay with a shiny $20 coin but has to pay with two $10 coins she received. It’s similar with Bitcoin: if I have received 1 Bitcoin from one place and 2 from another, I cannot just pay 3 Bitcoins but instead has to pay 1 + 2 bitcoins. The Bitcoin transactions are a bit like coins: when you give Bitcoins to somebody else, they cannot just be added together: the recipient has to use the coins you gave them in the first place.

Now, consider that Britney has to pay a fee depending on the weight of the coins she uses at Starbucks. That’s the Bitcoin transaction fee. If the fee for a $10 coin is more than $10 it is effectively worthless. And that’s the situation at Bitcoin right now: the transaction fee for using any coin is around $10-$20 right now. That means that even though you have $1000 in your Bitcoin wallet if it is made up of 100 payments of $10, you cannot spend any of it without the transaction fee eating all of it. The $50 is a rule of thumb, and you really have to pay fees depending on the “weight” of the “coins” you have received. It’s like US pennies, which cost more to produce than they are worth, except it’s everything below $20 and you have to pay the price each time you use them, not just once to make them.

Bitcoins do not exist like numbers in a bank account. A better (and simultaneously worse) analogy is physical coins, but the reality is that you spend transactions, not a balance. You can, of course, split up a transaction (or combine it), corresponding to exchanging two $10 coins for a $20 coin in a bank, but that too is a transaction with a fee…

Misconception 6: Bitcoin is Anonymous

Many seem to think that using Bitcoins is anonymous. They seem to have misunderstood the public part of a decentralized public ledger. All transactions are visible to all. Furthermore, most transactions go between Bitcoin wallet which has addresses (approximately, see next misconception for why that’s not entirely true). That means that as soon as you know a wallet address, you can follow all transactions into and out of that wallet. Capture a not-drug dealer? You can follow all transactions they ever made, and all transactions made to them. If you ever transferred drug money to a drug dealer? No takesies-backsies and it is visible in public forever to anybody. That’s the reason it was easy for the media to report how many people had paid for the WannaCry ransomware: they just looked up all transactions in the public ledger.

Many seem to think that using Bitcoins is anonymous. They seem to have misunderstood the public part of a decentralized public ledger. All transactions are visible to all. Furthermore, most transactions go between Bitcoin wallet which has addresses (approximately, see next misconception for why that’s not entirely true). That means that as soon as you know a wallet address, you can follow all transactions into and out of that wallet. Capture a not-drug dealer? You can follow all transactions they ever made, and all transactions made to them. If you ever transferred drug money to a drug dealer? No takesies-backsies and it is visible in public forever to anybody. That’s the reason it was easy for the media to report how many people had paid for the WannaCry ransomware: they just looked up all transactions in the public ledger.

Bitcoin is at best pseudonymous: you do not (necessarily) have names of each wallet, but you do have a unique identifier. Sometimes, the pseudonym is even better than known than the real person (if you know who Samuel L. Clemens is, raise your hand; if you’ve ever read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, raise your hand – did you know the latter was written by the former, or did you know it under his pseudonym Mark Twain?), and sometimes the pseudonym is publicly known (I think everybody thinks of The Running Man as a Stephen King novel even though it’s written by Richard Bachman). In the same way, you can see how many Bitcoins some exchanges have on hand because their pseudonyms are known.

Misconception 7: Bitcoin Addresses Exist

Most think of Bitcoin transactions as being between Bitcoin wallets which has addresses that look like 1F1tAaz5x1HUXrCNLbtMDqcw6o5GNn4xqX (as mentioned above, Bitcoin is not anonymous and that’s why you can follow all money to the not-drug site Silk Road). That’s not really true either. Bitcoin actually has smart contracts, but since that’s a very bad idea, they only accept any of a handful of predefined ones. One of these introduces the concept of a Bitcoin address. Another less used type allows you transfer money if, say, 2 out of 3 authorized people sign a transaction.

Most think of Bitcoin transactions as being between Bitcoin wallets which has addresses that look like 1F1tAaz5x1HUXrCNLbtMDqcw6o5GNn4xqX (as mentioned above, Bitcoin is not anonymous and that’s why you can follow all money to the not-drug site Silk Road). That’s not really true either. Bitcoin actually has smart contracts, but since that’s a very bad idea, they only accept any of a handful of predefined ones. One of these introduces the concept of a Bitcoin address. Another less used type allows you transfer money if, say, 2 out of 3 authorized people sign a transaction.

That means Bitcoin could be anonymous, it just chose not to. That also means that Bitcoin transactions are unnecessarily complex, because you actually have to check a smart contract. This keeps the transaction limit is artificially low when it wouldn’t need to be. One of the approved smart contracts depends on a bug in early versions of Bitcoin, so that bug can never be fixed. Bitcoin has a lot of these decisions that are perpetuated as the “only possible solution,” but are really just random situational decisions because Bitcoin is a proof-of-concept, so anytime somebody mentions Bitcoin has this and that and that’s the only correct choice, you can now think about how Bitcoin is a bunch of random choices, some of which are good and some of which are very, very bad.

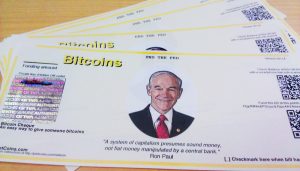

Misconception 8: No Trust is Necessary

Bitcoiners like to talk about how Bitcoin means we don’t have to trust anybody. As if that Randian dystopia was a good thing. No need to trust governments or federal banks.

Bitcoiners like to talk about how Bitcoin means we don’t have to trust anybody. As if that Randian dystopia was a good thing. No need to trust governments or federal banks.

No, instead you have to trust that Chinese money launderers process your transactions instead of just mining empty blocks because that gives them an advantage (that happened) or that they stick to the mining reward limit (which as outlined in misconception 4 they have absolutely no incentive to).

Really, Bitcoins are so expensive to use (see misconception 5), that most Bitcoin transactions actually happen off-chain. Instead of transferring Bitcoins from your wallet to other wallets, you transfer all your Bitcoins to the wallet of a Bitcoin exchange. You then get an IOU on the site saying you have, say, 7 Bitcoins, and can now sell them to other users of the site. This comes with the advantage that payments can be quick and cheap (you do not have to wait for the miners to pick up your transactions and pay them for the privilege), but on the other hand, you now trust that the exchange doesn’t just run away with your Bitcoins. Because that has happened. Oh, and instead of being anonymous, you have to transfer what is known as an identity theft starter kit worth of information. And if the exchange it not outright criminal, you are counting on them being sufficiently competent to securely store your data. Which experience shown several of them are not. And if any of this breaks, the exchanges are not really regulated, so the authorities are not likely to provide any oversight or help.

So, instead of trusting a number of highly educated economists whose job is to make sure the economy runs, and who are explicitly not personally incentivized to make decisions contrary to this, you have to trust a number of proven criminals who have all incentives to screw you.

Misconception 9: Bitcoin is Distributed

Another misconception is that Bitcoin is a distributed public ledger or something to that effect. It is not. Bitcoin is a decentralized replicated public ledger. Decentralized means that it does not live on a centralized server: anybody can in principle add to it. Replicated means that it is copied in full in a lot of places. Distributed means that parts of it put in different place. There’s a very big difference. Replication means it is fast to read data for everybody, but expensive to write data. Distributed means that it is fast to read and write data that is “close to” you, but it takes a long time – might even be impossible – to read/write data that is not. The replicated nature of the blockchain means that it is fast to see how many Bitcoins you (or anybody else) have, but takes forever to spend them.

Think of it this way: if I spend a Bitcoin buying a bunch of certainly not drugs, because Bitcoiners keep telling me that is possible, here in the Netherlands, and a Japanese guy spends a Bitcoin buying definitely not suspicious tentacly pornography, because you can get so many real goods that are not just weird pornography with Bitcoin, there’s no reason those two transaction should ever be synchronized. They are entirely unrelated and will never cross. Storing the Dutch not-drug transactions on a server in the Netherlands and the Japanese not-porn transaction on a server in Japan is a very good idea. A distributed system is a good way to deal with money. If I travel to Japan and start spending money buying not-porn there, there needs to be some synchronization as my money comes from the Dutch server, but this is a rare occurrence and waiting for an extra few seconds the first time while the Dutch server is contacted from Japan is probably acceptable. Bitcoin does not work that way. Instead, my not-drugs purchase in the Netherlands has to be sent to the Dutch server and to the Japanese server. Similarly, the Japanese not-porn purchase has to be sent from Japan to the Dutch server. And they have to agree that the not-drugs and not-porn purchases are unrelated. Every single time anybody anywhere buys anything. As we are told is totally a possibility because it is possible to spend Bitcoin in many places. That’s incredibly slow and inefficient, and impossible to scale.

Think of it this way: if I spend a Bitcoin buying a bunch of certainly not drugs, because Bitcoiners keep telling me that is possible, here in the Netherlands, and a Japanese guy spends a Bitcoin buying definitely not suspicious tentacly pornography, because you can get so many real goods that are not just weird pornography with Bitcoin, there’s no reason those two transaction should ever be synchronized. They are entirely unrelated and will never cross. Storing the Dutch not-drug transactions on a server in the Netherlands and the Japanese not-porn transaction on a server in Japan is a very good idea. A distributed system is a good way to deal with money. If I travel to Japan and start spending money buying not-porn there, there needs to be some synchronization as my money comes from the Dutch server, but this is a rare occurrence and waiting for an extra few seconds the first time while the Dutch server is contacted from Japan is probably acceptable. Bitcoin does not work that way. Instead, my not-drugs purchase in the Netherlands has to be sent to the Dutch server and to the Japanese server. Similarly, the Japanese not-porn purchase has to be sent from Japan to the Dutch server. And they have to agree that the not-drugs and not-porn purchases are unrelated. Every single time anybody anywhere buys anything. As we are told is totally a possibility because it is possible to spend Bitcoin in many places. That’s incredibly slow and inefficient, and impossible to scale.

On the upside, I can check very quickly how many Bitcoins I have, and how many Bitcoins everybody else has. Which is, of course, a thing I do all the time instead of spending them like a normal person.

Misconception 10: No Chargebacks

The final (and therefore according to the post title seventh) misconception is that Bitcoin inherently doesn’t have chargebacks. As if that were a good idea. There’s actually two ways in which this is wrong: First, a transaction is only final on the blockchain when there is no chance of it being overwritten, and until then can be overruled, in effect doing a chargeback. Second, there is nothing inherent in Bitcoin that doesn’t allow adding a special chargeback transaction.

Due to the nature of Bitcoin, it is possible for a block that has been added to the blockchain to be replaced if somebody else mines more blocks. This becomes less and less likely as more blocks are added, and means that if one or two blocks have been added it is pretty safe to assume the transaction stays, and typically one expects that after 6 blocks it is safe. At 10 minutes per block, that means a transaction time of at least 60 minutes of waiting time if there’s no backlog of transactions and your transaction has a sufficiently high fee to be included immediately. Of course, that’s assuming we are not in a situation with a split like under misconception 4; if we are, your transaction can be charged back even two weeks after you have made the payment.

Second, people say that the blockchain is immutable. That’s not the case at all. It’s an append-only storage (assuming we are not in the above case). Immutable means you cannot change it and append-only means you cannot change what has already been written. That doesn’t mean you cannot make a transaction saying “I roll back the previous transaction.” Bitcoin doesn’t presently support this (it kind-of does using smart contracts, but that feature is mostly switched off), but there’s no reason people wouldn’t add it. It has many uses, and just like misconception 4, all that’s needed is that a majority decides this is now a thing. Such a thing can be added entirely backwards compatible, so there’s really no reason that this won’t happen. Especially if somebody stands to gain from it. But that won’t happen – just trust people who has an incentive to screw you over not to do that ( ehm, I mean: no trust is necessary!).

Conclusion

This is just an off-the-top-of-my-head list of misconceptions I have run into. It’s a mixed-bag of just amusing misconceptions from people using technobabble without understanding what they talk about to fundamental assumptions that are just not correct.

Bitcoin is a complex product. It’s not even a product, it’s a proof-of-concept. Many of the people advocating it don’t even understand it, or have learned about it from others that do not understand it, and this leads to more or less fundamental misconceptions.

I hope this has given you a bit of insight into some of the pitfalls, and that people who tell you about Bitcoin don’t necessarily have their facts straight. In my opinion the biggest danger is that instead of trusting governments and federal banking systems without a personal interest in fucking you over, Bitcoin advocates instead trust more or less criminal entities with an explicit interest in fucking you over, and many don’t even understand this is what they do.

If you have other misconceptions, let me know in the comments. Also, let me know if you think I have made a mistake – I know that in some places I have over-simplified and have probably made one or two mistakes in my reasoning.

E: clarified that there is a bit of public key encryption in misconception 1, removed mentions about artificially inflating difficulty of cryptographic hash functions, and changed from miners signing transactions to just checking them in misconception 4.